As the pace of COVID-19 vaccinations accelerates and states loosen restrictions, employers have slowly begun calling their employees back to the workplace, with the pace expected to pick up sharply over the next few months. But what might have been a hopeful sign that life is returning to normalcy has instead become a source of friction as some workers push back. They are fearful of getting infected, worried about how to care for kids still learning remotely and resisting going back to the 9-to-5 in-office grind after tasting the flexibility of working from home.

While 83 percent of CEOs want employees to return in person, only 10 percent of employees want to come back full time.

How these conflicts play out could define the shape of the employment landscape not just in the near term but for years to come, experts say, as employers and workers begin negotiating the terms of re-engagement. For now, they are oceans apart: While 83 percent of CEOs want employees to return in person, only 10 percent of employees want to come back full time, according to a study by the Best Practice Institute.

"This is going to be a major flash point," says Melissa Swift of the management consulting firm Korn Ferry. "There is a belief in our culture that we've proven that most jobs can be done virtually. But that's not the belief within the leadership of organizations, so we're headed for a real clash."

Workplace safety is a major concern. Although all adults will now be eligible for vaccination by April 19 under President Joe Biden's newly accelerated timeline, the nation is a long way from herd immunity: Nearly two-thirds of Americans still have not received even one dose and only 20 percent of the population has been fully vaccinated. And with variants spreading, COVID-19 cases are on the rise again in most states across the country.

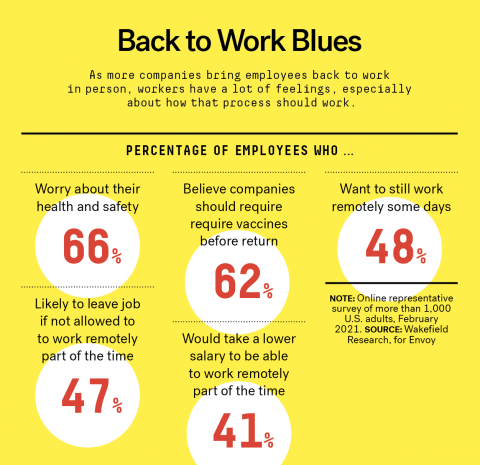

As companies shove desks apart, install plexiglass dividers and stagger work schedules, some 66 percent of employees are worried about the health risks of returning to the office, according to Wakefield Research in a March study sponsored by Envoy; a mere 13 percent say they're not concerned at all. Meanwhile, more than six in 10 workers believe companies should make getting a vaccine mandatory before employees are allowed back in the office—roughly the same number who fear their employer will relax COVID-19 safety measures too soon.

The School Conundrum

Among the anxious is Jamie Hickey, a 42-year-old single dad with two daughters, ages nine and six, who learn from home three days a week. A supervisor for a Philadelphia office-furniture company, he has been called back to work full time starting April 15 after being furloughed last spring. After subsisting for a year on unemployment compensation and revenue from two hobby websites, he is eager to return to work. But he fears going on installation jobs inside commercial buildings and schools that may not be following proper safety protocols.

Hickey is also worried about who will look after his girls on the days they're not physically at school. He could ask his 60-year-old mother but is concerned about her health risks because she hasn't gotten the vaccine yet. He has proposed working on blueprints from home but his bosses want him out in the field. "I'm not worried about dying myself," he says. "I'm worried about passing the virus to somebody else, like my kids or my mom, who has underlying conditions."

The back-to-the-office calculus is especially complicated for parents like Hickey, with younger children at home whose schools are not fully open for in-person learning or for whom childcare arrangements are not back to normal. The big question is: Who will take care of the kids while Mom and Dad are away at work?—a challenge that becomes even more fraught in single-parent households.

Surveys show far more schools now offer full-time in-person instruction than earlier in the pandemic but the situation is still nowhere close to the pre-COVID status quo. According to federal data, just under half of public schools are now open for full-time in-person classes for elementary school students and 38 percent are open for middle schoolers, with more open in the South and Midwest than the Northeast and West. About one in four districts offer no in-person classes at all.

Far fewer students are attending school in person than the percentage of schools that are open, though, perhaps due to parents' concerns about safety. The federal data shows that 60 percent of fourth graders and 69 percent of eighth graders were still learning from home at least part of the time in February, underscoring the difficulty for parents who may be called back to the office soon. It's particularly challenging for families of color: The same data shows that while more than half of white fourth graders were back to school in person full time, only 30 percent of Black students and 32 percent of Hispanic children were.

Returns Picking Up Steam

For now, the tug-of-war between employers and workers is still in its early stages. Office occupancy rates remain low at 24 percent nationwide as of late March, according to Kastle Systems, a building security company with customers in more than 2,600 buildings in 138 cities across the U.S. But that's a substantial increase from the under-15 percent rate of a few months ago. And that number is expected to continue rising in the coming months as more organizations announce their return-to-workplace plans.

In New York City, for example, Mayor Bill de Blasio recently announced a target date of May 3 for about 80,000 municipal office workers to return to their offices. While overall, only 14 percent of the city's office workers are back to in-person work according to Kastle, a recent survey by the Partnership for New York City shows that 45 percent are expected to return by September. In cities like Houston and Dallas, office occupancy rates have been rising sharply in recent weeks, as COVID-19 cases in Texas dropped, and are now at or above 35 percent.

The question, though, is not just when companies will bring workers back to the office but under what arrangements—in person every day or a hybrid schedule that allows employees to work remotely some of the time.

Some large companies have made it clear they will bring everybody back to an in-person setting full time. Amazon expects to end its remote-work arrangements by fall, it says, and "return to an office-centric culture as our baseline." Goldman Sachs agrees. Remote work is "not a new normal," CEO David Solomon told an industry conference in February. "It's an aberration that we're going to correct as soon as possible."

Other employers, especially tech companies, are being more flexible. Microsoft, Facebook and Twitter are all giving staff members the option of working remotely on a permanent basis. Salesforce, after polling its employees, now says that most of its staffers can come into the office just one to three days per week; those who live far away can work remotely indefinitely. "An immersive workspace is no longer limited to a desk in our Towers; the 9-to-5 workday is dead," the company said in a blog post announcing the change.

Caught in the middle are workers trying to find their place in a job market transformed by the virus. More than half of workers (55 percent) say they want to be remote at least three days a week, according to a survey by PwC, but most executives, especially outside of the tech industry, don't much like that idea: Only a quarter say they will allow employees to work remotely for a significant amount of time.

"Companies always want to see for themselves how people are working to reduce the risk that they are being inefficient," says Anita Williams Woolley, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business. "Sometimes that's related to the belief that if people are physically co-located they can collaborate and innovate more easily."

At Odds Over Productivity

The vast majority of employees believe they are more productive working from home, surveys show. One of them is Shantay Williams, a 34-year-old program manager at the University of Alabama at Birmingham's School of Nursing. When the pandemic struck, she kept up her regular duties from home, she says, plus a host of new tasks created by the public health emergency. In October, she was called back two days a week and will soon have to rejoin the Monday-Friday rat race full time, battling traffic two hours a day.

"I told my supervisor that going back to the office is stupid," she says. "I'm very vocal about it. And they know I'm doing the work because they're getting emails from me at 10, 11 o'clock at night."

By contrast to what workers say, about half of executives do not believe their workers have been more productive since going remote. At Bank of America, chief operations and technology officer Cathy Bessant says company data reveals that its remote workers have produced less and are more error-prone, partly due to not having co-workers nearby to catch mistakes.

Working from home can also result in longer hours, surveys show, and that can lead to burnout. At a conference last fall, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said blending work and home life means "it sometimes feels like you are sleeping at work."

Pre-pandemic efforts to prove either side of the productivity debate have largely failed. Proponents of remote work often point to a 2015 study led by Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom showing that the job performance of Chinese call-center employees rose by 13 percent when they worked from home and they were also half as likely to quit or be fired. Detractors say these findings do not apply to jobs that require collaboration and prove only that such independent work should be shifted to remote freelancers, allowing the company to save on office space and benefits like health insurance.

"When companies like Salesforce allow people to work from home, they're often looking to get rid of their offices," says Peter Cappelli of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, noting that goal was the motivation of the firm in the China study. "Companies might conclude that those real-estate savings are higher than any hit they might take in productivity or innovation by letting people work from home. But to be honest, I think they don't really know."

The Hybrid Solution

For many employees, working from home during the pandemic has given them the flexibility to devote more time to family, exercise, self-care, hobbies, even side hustles. Gaining back the two hours she used to spend commuting every day, for example, has given Williams time to show houses for her growing sideline real estate business. Heather Cooprider, a marketing manager in Atlanta, Georgia, has established a healthy morning routine of meditating, taking a walk and eating breakfast that she says makes her much happier and more focused than before, when it was a daily scramble to get to the office. Neither is eager to give up their newfound freedom.

On the other hand, too much solitude or family togetherness has made some employees eager to spend at least part of the week back at the office. Younger workers especially seem to crave some on-the-premises time to absorb the company culture and benefit from mentorship.

Overall, 90 percent of employees miss some aspect of their workplace, Wakefield Research found in October, especially being with friends and teammates (47 percent), small talk at the coffee machine or water cooler (31 percent), and perks like lunch and snacks (36 percent).

The number of days workers want to spend in the office varies widely, creating a scheduling headache for managers who try to accommodate their staffs. According to the PwC study, 28 percent of employees want to work remotely five days a week, 35 percent prefer two or three days, 10 percent four days, and 10 percent one day. Only 8 percent wanted to come to the office full time.

And if they don't get what they want? A Harris Poll commissioned by ClickUp showed that 54 percent of employees say they will refuse to work for a company that doesn't offer the flexibility of working remotely at least some of the time.

But being out of the office too much can be perilous, management experts say: Studies show remote workers earn less respect; are not as involved in important decisions; do not get promoted as often; have worse office relationships; and do not get credit for putting in long hours.

If the boss says you must come back in the office, in most cases you don't have much legal recourse, even during a pandemic. The federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which updated its guidance for employers in June, says employees cannot refuse to return to the workplace because of a general fear of contracting COVID-19.

They can, however, ask to work remotely if they have a condition covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act (needing to work remotely to care for family members in ill health may be covered by the Family and Medical Leave Act). Under federal and state laws, employers must take appropriate safety precautions, which may include requiring face masks. Caring for children at home is the employees' responsibility, though if their regular paid child care provider is not available because of COVID-19, they may be entitled to up to 12 weeks of paid leave (with a maximum of $200 per day) under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act.

For employers, managing a staff during a public health emergency is an enormous challenge—balancing remote and in-person scheduling to accommodate a wide range of employee needs, putting co-workers who need to be in the office at the same time together and making remote workers feel like a valued part of the team. Companies that solve these puzzles will have a distinct competitive advantage in recruiting talent, says Dan Helfrich, chief executive of Deloitte Consulting, who tries to practice what he preaches: In recent months, Deloitte has staged dozens of Zoom debates to hear how employees feel about working remotely versus in person. "Organizations that have a more empowered, trusting way to consider the diversity of viewpoints on their team and create a future that accommodates them are the ones that will win," he says.

People who love their workplaces are up to four times more likely to perform at a higher level than those who do not, research shows.

Research would seem to back him up. In a global survey of employees from Fortune 1000 companies, Louis Carter of the Best Practice Institute showed that people who love their workplaces are up to four times more likely to perform at a higher level than those who do not. "There are pages of literature showing a strong connection between employee happiness and productivity," says Carter.

As the pace of vaccinations picks up, employers are busy crafting back-to-workplace policies that assume health risks will decline—and hoping that virus variants and reckless behavior don't trigger a fourth wave. Some are guided by Helfrich's pledge to employees—"Your well-being is greater than Deloitte's well-being"—while others share the view of Bank of America's Bessant, who told Forbes that, when it comes to remote work, "The needs of the many win against the desire of the individual. The collective role of the firm should drive our choices."

For now, says Wharton's Cappelli, "Companies are all looking at each other trying to see who will bring people back first, and what kind of negative PR they get. That will dictate how quickly the others follow."

Employees like single-dad Hickey and several of his co-workers can only hope their manager is listening as they plead to wait until conditions are safer before calling them back. "My boss has been hinting that they're getting enough heat that she may need to look at this again, but that's all I've got to go on," he says. "If she wakes up in a bad mood, who knows?"

In other words, the employer holds all the cards. As the workplace battle rages, if you don't play ball, your boss can always find someone who will.

Paul Keegan is a freelance writer and co-author, with City Winery founder Michael Dorf, of Indulge Your Senses: Scaling Intimacy in a Digital World. He has also written for The New York Times Magazine, Esquire, GQ, Fortune, Inc. and Outside.